Cuba 2018: Neo-Castroism and an Economy in Hibernation. By Iván García. Translating Cuba.

Cuba 2018: Neo-Castroism and an Economy in Hibernation

By Ivan Garcia

Translating Cuba

January 5, 2019

(Foto: Ernesto Pérez Chang - Cubanet )

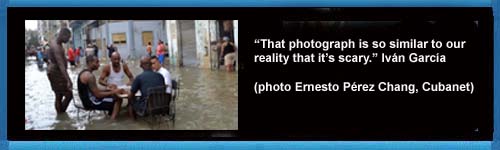

There is no better country in which to find a surrealist atmosphere than Cuba. In October of 2017, when the hurricane winds of Irma ruined whatever was in their way, a photo that went around the world explained the political nonsense and citizens’ indifference.

The waters of the Atlantic Ocean jumped the wall of the Havanan seawall and in association with the Macondian* downpours flooded the poor neighborhoods of the capital such as Colón, San Leopoldo, Jesús María, Belén and Los Sitios.

Havana collapsed, people ransacked the hard currency markets and at a table in the middle of a street flooded with dirty water, four imperturbable men played dominoes and drank rum, while a part of the island collapsed. That photograph is so similar to our reality that it’s scary.

Two months after the passage of the cyclone, in January 2018, in an imitation of elections, the 168 municipal assemblies, by sheer citizen resignation, elected 605 candidates** for deputies to the Cuban parliament.

On April 19, the National Assembly of Peoples Power chose the future president. Abroad, the news was that the new ruler did not have the surname Castro. But, to our disgrace, the day after being proclaimed, Miguel Mario Diaz-Canel Bermudez promised more Castroism, economic planning and ironclad state control in every part of civic life.

That morning, after being proclaimed president, Díaz-Canel, somewhat embarrassed and shy, read the worst speech in memory from an elected president. “I promise nothing,” summed up in his disastrous presidential strategy. And he declared himself a fervent follower of Fidel Castro and “compañero Raúl.” More transparent and sincere he could not be.

Born in Placetas, Villa Clara, on April 20, 1960, Díaz-Canel never sold himself as a reformer or a high-caliber statesman. In any case, he is a figurehead. A guy without complexes, he says that every morning he receives advice from his political manager, Raúl Castro. He is a pragmatic politician. He is very familiar with how the ship sinks.

But trained by the old Fidelist school of resisting until the last breath. He will not proclaim major economic and political changes if the people do not demand it. Castroism is not an ideology, it is not even a political theory. It is a brotherhood of officials, soldiers and bureaucrats who benefit most if they renounce democracy.

If Castroism has not worked in 60 years, the neo-Castroism or late Castroism represented by Diaz-Canel is very unlikely to work. Castro I’s style of government was characterized by his inability to decentrally administer public service, produce food, economically develop the nation and bring prosperity to the citizens. But if something stood out it was in the management of diplomacy, in social control and the repression of opponents.

In the first eight months, Díaz-Canel was in exploration mode. He showed up at the place where a passenger plane crashed in Havana and visited the Batabanó municipality after a storm caused flooding. He often dissects the dissimilar structural problems of the peculiar Cuban system and his only promise, which sounds like a bluff, has been to ensure that in ten years he will solve the housing deficit in the country. We will have to wait and see.

For ordinary people, Diaz-Canel is opaque and his speeches are boring. On his tours of different cities and municipalities of the Island he shows himself as an indistinct bettor on the populism that used to be carried out by Fidel Castro.

In present-day Cuba, investments in public infrastructure are minimal. If anything, money is spent on improving water networks and a cheap coat of paint in hospitals. The construction of children’s centers, new health and educational centers is not planned. Transportation is chaos.

It is difficult for an institution administered by the State to have a passing grade. What works best in Cuba comes from the private sector. Restaurants, bars, hairdressers. But since the summer of 2017, the regime has reversed the reforms of self-employment. Why? A municipal party official we will call Óscar offers the answer.

“Self-employment was always seen as something conjunctural. If economic reforms were implemented in 2010 and self-employment expanded, it was for the simple reason that the State needed to get one and a half million people off the employment rolls. But only half a million left. It was thought that with the fiscal siege and the control of the inspectors, private work would not grow too much. But it was shown that when working for his or her own benefit, the individual is able to overcome any barrier. Self-employment has managed to overcome the shortages and lack of a wholesale market with creativity, circumventing tax rules and importing under the table. Today nobody dines in a state restaurant, they go to a paladar (private restaurant). And in other sectors they also offer strong competition to the State,” says the source and he concludes:

“Obama’s political strategy of importing and granting credits to self-employed people has intimidated the government. If that sector continued to grow at the stroke of dollars, in a short time it could cause economic changes of greater depth, and even political. The State sees them as a Trojan Horse. An enemy rather than a friend. Thousands of professionals have left their careers to become private entrepreneurs, which worries the government and that is why it seeks greater control over self-employment.”

The Cuba of 2018 was pure gatopardismo***. Make changes, without anything changing. The economy is still in recession. The optimistic television presenters announce productive growth that never lands on the table of Cuban families. Food prices rose between 10 and 25 percent. Hard currency markets are more undersupplied than ever. Recent statements by Alejandro Gil, Minister of Economy and Planning, suggest that there is no possibility of reversing the situation in 2019.

Between October and November, Miguel Diaz-Canel and his wife Lis Cuesta, on official visits, toured China, Russia, North Korea, Vietnam and Laos with a brief stopover in London. Nobody opened their wallets. Putin coiled himself in the same position: invest ten percent of debt forgiven to Cuba in the railroad and power plants and sell arms. China prefers to wait. He sees no short-term return. Publicly he offers the discourse from his fellow travelers, although the money is still at home. North Korea and Laos were ideological visits. Vietnam pushes him to the market economy, but Castroism thinks about it.

The olive-green autocracy desperately seeks foreign investment. In October 2018, Cubadebate reported that the Mariel Special Development Zone attracted 474 million dollars, the largest amount of investment in five years. Emilio Morales, president of the Havana Consulting Group, estimates that this figure is five times lower than the investments of the mules that travel to buy goods from Russia, Haiti, Mexico or Panama, which they then sell on the Cuban black market.

It is evident that the Havana regime lives in another dimension. Díaz-Canel wants to promote electronic government and create computerized mechanisms so that the population can exchange with state officials and manage their problems with immediacy. He announced the opening of a government website and a channel on You Tube. And he asked that all ministers open accounts on Twitter and be active on social networks.

“In what country does ‘Canelo’ live? One hour of internet in any wifi zone costs one convertible peso and mobile internet data, the cheapest available, costs seven CUC. He believes that people will spend a third of their monthly salary to chat with ministers and officials who resolve nothing. It’s ridiculous. If you want to interrelate with the people, let the ministers get out of their cars and without warning, walk around the streets and learn about the problems of the people. Let them get down and dirty with the people, not that staging they put on when a leader visits a place,” says Camila, a university student.

The worst thing about the Cuba of 2018 is not the shortage of bread and eggs, or that the price of pork rises steadily or how difficult it is to buy milk powder in hard currency stores. No. What scares people the most is the lack of a future. There are no solutions in sight.

If you travel through the poor and mostly black neighborhood of Los Sitios, in the heart of Havana, you will hear full-fledged reguetón blasting through the phones and observe the habitual passivity of Cubans who specialize in the art of waiting. There, between houses in danger of collapse and street hawkers, Yosvany Sierra Hernández, alias Chocolate MC, was born, an aggressive and defiant reguetonero who, despite the bans and prohibitions of the Ministry of Culture and state media, is heard openly throughout the Island.

Without spending a dime on advertising, Chocolate is more popular than Miguel Díaz-Canel. It’s the Cuba that nobody understands.

Translator’s notes:

*A reference to the fictional town of Macondo in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novels.

**There were 605 names on the ballots for the 605 positions.

***”Everything changes so that everything remains the same.” See “The Leopard,” a novel by Lampedusa.